C. Aubrey Smith on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

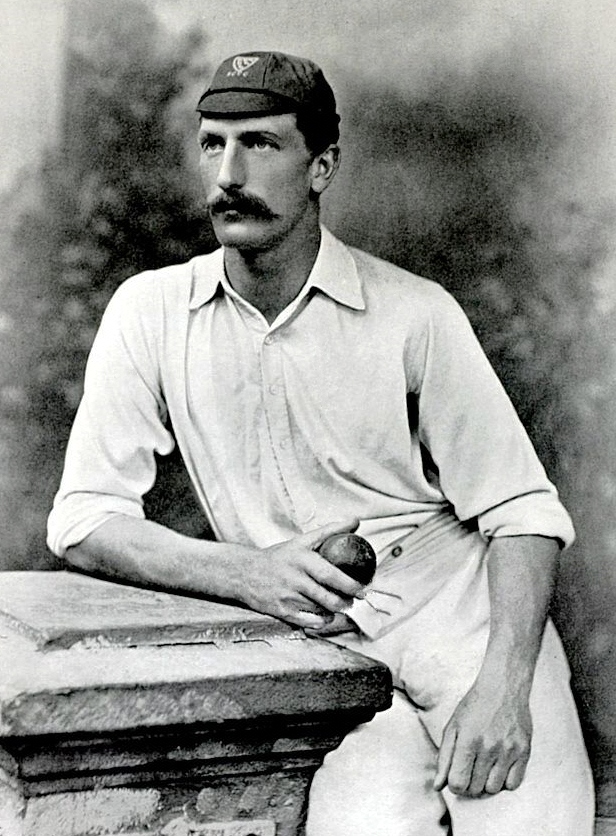

Sir Charles Aubrey Smith (21 July 1863 – 20 December 1948) was an English Test cricketer who became a stage and film actor, acquiring a niche as the officer-and-gentleman type, as in the first sound version of '' The Prisoner of Zenda'' (1937). In Hollywood, he organised British actors into a cricket team, much intriguing local spectators.

As a cricketer, Smith was primarily a right arm fast bowler, though he was also a useful right-hand lower-order batsman and a good slip fielder. His oddly curved bowling run-up, which started from deep mid-off, earned him the nickname "Round the Corner Smith". When he bowled round the wicket his approach was concealed from the batsman by the umpire until he emerged, leading W. G. Grace to comment "it is rather startling when he suddenly appears at the bowling crease." He played for Cambridge University (1882–1885) and for

As a cricketer, Smith was primarily a right arm fast bowler, though he was also a useful right-hand lower-order batsman and a good slip fielder. His oddly curved bowling run-up, which started from deep mid-off, earned him the nickname "Round the Corner Smith". When he bowled round the wicket his approach was concealed from the batsman by the umpire until he emerged, leading W. G. Grace to comment "it is rather startling when he suddenly appears at the bowling crease." He played for Cambridge University (1882–1885) and for

Smith began acting on the London stage in 1895. His first major role was in ''

Smith began acting on the London stage in 1895. His first major role was in ''

The Home of CricketArchive

Cricketarchive.com (20 December 1948). Retrieved on 2018-05-19.Obituary '' Variety'', 22 December 1948, p. 55.

Stage performances in Theatre Archive University of Bristol"C. Aubrey Smith – Hollywood's Resident Englishman" by Ken Robichaux

{{DEFAULTSORT:Smith, C. Aubrey 1863 births 1948 deaths Cambridge University cricketers England Test cricketers English male film actors English male silent film actors English male stage actors English expatriate male actors in the United States Actors awarded knighthoods Cricket people awarded knighthoods Cricketers who have taken five wickets on Test debut Knights Bachelor Commanders of the Order of the British Empire England Test cricket captains English cricketers Sussex cricket captains Sussex cricketers People from the City of London Gauteng cricketers Gentlemen cricketers North v South cricketers Legion of Frontiersmen members Deaths from pneumonia in California People educated at Charterhouse School Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge 19th-century English male actors 20th-century English male actors Marylebone Cricket Club cricketers Gentlemen of England cricketers Cricketers who have acted in films Cricketers from Greater London Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer contract players Male actors from London

Early life

Smith was born in London, England, to Charles John Smith (1838–1928), a medical doctor, and Sarah Ann (''née'' Clode, 1836–1922). His sister, Beryl Faber (died 1912), was married to Cosmo Hamilton. Smith was educated atCharterhouse School

(God having given, I gave)

, established =

, closed =

, type = Public school Independent day and boarding school

, religion = Church of England

, president ...

and St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge founded by the House of Tudor, Tudor matriarch Lady Margaret Beaufort. In constitutional terms, the college is a charitable corpo ...

.Wills, Walter H., 1907. ''The Anglo-African Who's Who'', Jeppestown Press, United Kingdom. p. 337. He settled in South Africa to prospect for gold in 1888–89. While there he developed pneumonia and was wrongly pronounced dead by doctors. He married Isabella Wood in 1896.

Cricket career

As a cricketer, Smith was primarily a right arm fast bowler, though he was also a useful right-hand lower-order batsman and a good slip fielder. His oddly curved bowling run-up, which started from deep mid-off, earned him the nickname "Round the Corner Smith". When he bowled round the wicket his approach was concealed from the batsman by the umpire until he emerged, leading W. G. Grace to comment "it is rather startling when he suddenly appears at the bowling crease." He played for Cambridge University (1882–1885) and for

As a cricketer, Smith was primarily a right arm fast bowler, though he was also a useful right-hand lower-order batsman and a good slip fielder. His oddly curved bowling run-up, which started from deep mid-off, earned him the nickname "Round the Corner Smith". When he bowled round the wicket his approach was concealed from the batsman by the umpire until he emerged, leading W. G. Grace to comment "it is rather startling when he suddenly appears at the bowling crease." He played for Cambridge University (1882–1885) and for Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

at various times from 1882 to 1892.

While in South Africa he captained the Johannesburg English XI. He captained England to victory in his only Test match, against South Africa at Port Elizabeth

Gqeberha (), formerly Port Elizabeth and colloquially often referred to as P.E., is a major seaport and the most populous city in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is the seat of the Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan Municipality, Sou ...

in March 1889, taking five wickets for nineteen runs in the first innings. The English team who played were by no means representative of the best players of the time and nobody at the time realised that the match would enter the cricket records as an official Test match. His home club for much of his career was West Drayton Cricket club. Actors would arrive from London to the purpose-built train station in West Drayton and taken by horse-drawn carriage to the ground.

In 1932, he founded the Hollywood Cricket Club and created a pitch with imported English grass. He attracted fellow expatriates such as David Niven, Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the Theatre of the U ...

, Nigel Bruce (who served as captain), Leslie Howard and Boris Karloff to the club as well as local American players. Smith's stereotypical Englishness spawned several amusing anecdotes: while fielding at slip for the Hollywood Club, he dropped a difficult catch and ordered his English butler to fetch his spectacles; they were brought on to the field on a silver platter. The next ball looped gently to slip, to present the kind of catch that "a child would take at midnight with no moon." Smith dropped it and, snatching off his lenses, commented, "Damned fool brought my reading glasses." Decades after his cricket career had ended, when he had long been a famous face in films, Smith was spotted in the pavilion on a visit to Lord's

Lord's Cricket Ground, commonly known as Lord's, is a cricket venue in St John's Wood, London. Named after its founder, Thomas Lord, it is owned by Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) and is the home of Middlesex County Cricket Club, the England and ...

. "That man over there seems familiar", remarked one member to another. "Yes", said the second, seemingly oblivious to his Hollywood fame, "Chap called Smith. Used to play for Sussex."

Acting career

Smith began acting on the London stage in 1895. His first major role was in ''

Smith began acting on the London stage in 1895. His first major role was in ''Prisoner of Zenda

''The Prisoner of Zenda'' is an 1894 adventure novel by Anthony Hope, in which the King of Ruritania is drugged on the eve of his coronation and thus is unable to attend the ceremony. Political forces within the realm are such that, in orde ...

'' the following year, playing the dual lead roles of king and look-alike. Forty-one years later, he appeared in the most acclaimed film version of the novel, this time as the wise old adviser. When Raymond Massey

Raymond Hart Massey (August 30, 1896 – July 29, 1983) was a Canadian actor, known for his commanding, stage-trained voice. For his lead role in '' Abe Lincoln in Illinois'' (1940), Massey was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor. Amo ...

asked him to help him understand the role of Black Michael, he answered "My dear Ray, in my time I have played every part in ''The Prisoner of Zenda'' except Princess Flavia. And I always had trouble with Black Michael!" He made his Broadway debut as early as 1895 in ''The Notorious Mrs. Ebbsmith''. In 1907 he appeared with Marie Doro

Marie Doro (born Marie Katherine Stewart; May 25, 1882 – October 9, 1956) was an American stage and film actress of the early silent film era.

She was first noticed as a chorus-girl by impresario Charles Frohman, who took her to Broadway, whe ...

in ''The Morals of Marcus'', a play Doro later made into a silent film. Smith later appeared in a revival of George Bernard Shaw's ''Pygmalion

Pygmalion or Pigmalion may refer to:

Mythology

* Pygmalion (mythology), a sculptor who fell in love with his statue

Stage

* ''Pigmalion'' (opera), a 1745 opera by Jean-Philippe Rameau

* ''Pygmalion'' (Rousseau), a 1762 melodrama by Jean-Jacques ...

'' in the starring role of Henry Higgins.

Smith appeared in early films for the nascent British film industry, starring in ''The Bump'' in 1920 (written by A. A. Milne for the company Minerva Films, which was founded in 1920 by the actor Leslie Howard and his friend and story editor Adrian Brunel). Smith later went to Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywood, ...

where he had a successful career as a character actor playing either officer or gentleman roles. One role in 1937 was as Colonel Williams in ''Wee Willie Winkie'', starring Shirley Temple

Shirley Temple Black (born Shirley Jane Temple;While Temple occasionally used "Jane" as a middle name, her birth certificate reads "Shirley Temple". Her birth certificate was altered to prolong her babyhood shortly after she signed with Fox in ...

, Victor McLaglen, Cesar Romero and June Lang. He was regarded as being the unofficial leader of the British film industry colony in Hollywood, which Sheridan Morley characterised as the Hollywood Raj, a select group of British actors who were seen to be colonising the capital of the film business in the 1930s. Other film stars considered to be "members" of this select group were David Niven (whom Smith treated like a son), Ronald Colman

Ronald Charles Colman (9 February 1891 – 19 May 1958) was an English-born actor, starting his career in theatre and silent film in his native country, then immigrating to the United States and having a successful Hollywood film career. He wa ...

, Rex Harrison

Sir Reginald Carey "Rex" Harrison (5 March 1908 – 2 June 1990) was an English actor. Harrison began his career on the stage in 1924. He made his West End debut in 1936 appearing in the Terence Rattigan play ''French Without Tears'', in what ...

, Robert Coote, Basil Rathbone

Philip St. John Basil Rathbone MC (13 June 1892 – 21 July 1967) was a South African-born English actor. He rose to prominence in the United Kingdom as a Shakespearean stage actor and went on to appear in more than 70 films, primarily costume ...

, Nigel Bruce (whose daughter's wedding he had attended as best man), Leslie Howard (whom Smith had known since working with him on early films in London), and Patric Knowles.

Smith expected his fellow countrymen to report for regular duty at his Hollywood Cricket Club. Anyone who refused was known to "incur his displeasure". Fiercely patriotic, Smith became openly critical of the British actors of enlistment age who did not return to fight after the outbreak of World War II in 1939. Smith loved playing on his status as Hollywood's "Englishman in Residence". His bushy eyebrows, beady eyes, handlebar moustache, and height of 6'2" made him one of the most recognisable faces in Hollywood.

Smith starred alongside leading ladies such as Greta Garbo, Elizabeth Taylor

Dame Elizabeth Rosemond Taylor (February 27, 1932 – March 23, 2011) was a British-American actress. She began her career as a child actress in the early 1940s and was one of the most popular stars of classical Hollywood cinema in the 1950s. ...

, and Vivien Leigh

Vivien Leigh ( ; 5 November 1913 – 8 July 1967; born Vivian Mary Hartley), styled as Lady Olivier after 1947, was a British actress. She won the Academy Award for Best Actress twice, for her definitive performances as Scarlett O'Hara in ''Gon ...

as well as the actors Clark Gable, Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the Theatre of the U ...

, Ronald Colman

Ronald Charles Colman (9 February 1891 – 19 May 1958) was an English-born actor, starting his career in theatre and silent film in his native country, then immigrating to the United States and having a successful Hollywood film career. He wa ...

, Maurice Chevalier

Maurice Auguste Chevalier (; 12 September 1888 – 1 January 1972) was a French singer, actor and entertainer. He is perhaps best known for his signature songs, including " Livin' In The Sunlight", " Valentine", "Louise", " Mimi", and "Thank Hea ...

, and Gary Cooper. His films include ''The Prisoner of Zenda'' (1937), '' The Four Feathers'' (1939), Hitchcock's ''Rebecca

Rebecca, ; Syriac: , ) from the Hebrew (lit., 'connection'), from Semitic root , 'to tie, couple or join', 'to secure', or 'to snare') () appears in the Hebrew Bible as the wife of Isaac and the mother of Jacob and Esau. According to biblical ...

'' (1940), ''Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

Doctor is an academic title that originates from the Latin word of the same spelling and meaning. The word is originally an agentive noun of the Latin verb 'to teach'. It has been used as an academic title in Europe since the 13th century, w ...

'' (1941), '' And Then There Were None'' (1945) in which he played General Mandrake, and the 1949 remake of ''Little Women

''Little Women'' is a coming-of-age novel written by American novelist Louisa May Alcott (1832–1888).

Alcott wrote the book, originally published in two volumes in 1868 and 1869, at the request of her publisher. The story follows the lives ...

'' starring Elizabeth Taylor

Dame Elizabeth Rosemond Taylor (February 27, 1932 – March 23, 2011) was a British-American actress. She began her career as a child actress in the early 1940s and was one of the most popular stars of classical Hollywood cinema in the 1950s. ...

and Janet Leigh, in which he portrayed the aged grandfather of Laurie Lawrence (played by a young Peter Lawford), who generously gives a piano to the frail Beth March (played by Margaret O'Brien). He also appeared as the father of Maureen O'Sullivan

Maureen O'Sullivan (17 May 1911 – 23 June 1998) was an Irish-American actress, who played Jane in the ''Tarzan'' series of films during the era of Johnny Weissmuller. She performed with such actors as Laurence Olivier, Greta Garbo, William ...

in ''Tarzan the Ape Man Tarzan, the Ape Man may refer to

* Tarzan, a fictional character

* ''Tarzan the Ape Man'' (1932 film), with Johnny Weissmuller

* ''Tarzan, the Ape Man'' (1959 film) with Denny Miller

* ''Tarzan, the Ape Man'' (1981 film) with Richard Harris and ...

'', the first Tarzan film with Johnny Weissmüller

Johnny Weissmuller (born Johann Peter Weißmüller; June 2, 1904 – January 20, 1984) was an American Olympic swimmer, water polo player and actor. He was known for having one of the best competitive swimming records of the 20th century. H ...

. Smith also played a leading role as the Earl of Dorincourt in David O. Selznick

David O. Selznick (May 10, 1902June 22, 1965) was an American film producer, screenwriter and film studio executive who produced ''Gone with the Wind'' (1939) and ''Rebecca'' (1940), both of which earned him an Academy Award for Best Picture.

E ...

's adaption '' Little Lord Fauntleroy'' (1936).

He appeared in Dennis Wheatley

Dennis Yeats Wheatley (8 January 1897 – 10 November 1977) was a British writer whose prolific output of thrillers and occult novels made him one of the world's best-selling authors from the 1930s through the 1960s. His Gregory Sallust series ...

's 1934 thriller ''Such Power Is Dangerous'', about an attempt to take over Hollywood, under the fictitious name of Warren Hastings Rook (rather than Charles Aubrey Smith). Author Evelyn Waugh leaned heavily on Smith in drawing the character of Sir Ambrose Abercrombie for Waugh's 1948 satire of Hollywood ''The Loved One

''The Loved One: An Anglo-American Tragedy'' (1948) is a short satirical novel by British novelist Evelyn Waugh about the funeral business in Los Angeles, the British expatriate community in Hollywood, and the film industry.

Conception

''The ...

''. Commander McBragg in the TV cartoon ''Tennessee Tuxedo and His Tales

''Tennessee Tuxedo and His Tales'' is an animated television series that originally aired Saturday mornings on CBS from 1963 to 1966 as one of the earliest Saturday morning cartoons. It was produced by Total Television, the same company that prod ...

'' is a parody of him.

Death

Smith died of pneumonia at home in Beverly Hills on 20 December 1948, aged 85. He was survived by his wife and their daughter, Honor. His body was cremated and nine months later, in accordance with his instructions, the ashes were returned to England and interred in his mother's grave at St Leonard's churchyard in Hove,Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

.

Honours and awards

Smith has a star on theHollywood Walk of Fame

The Hollywood Walk of Fame is a historic landmark which consists of more than 2,700 five-pointed terrazzo and brass stars embedded in the sidewalks along 15 blocks of Hollywood Boulevard and three blocks of Vine Street in Hollywood, Californ ...

.

Smith was an officer in the Legion of Frontiersmen.

In 1933, he served on the first board of the Screen Actors Guild.

He was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1938 and was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

by George VI in 1944 for services to Anglo-American amity.Cricketarchive.com (20 December 1948). Retrieved on 2018-05-19.Obituary '' Variety'', 22 December 1948, p. 55.

Complete filmography

See also

* List of England cricketers who have taken five-wicket hauls on Test debutReferences

Further reading

* David Rayvern Allen, ''Sir Aubrey: Biography of C. Aubrey Smith, England Cricketer, West End Actor, Hollywood Film Star'', Elm Tree Books, 1982,External links

* *Stage performances in Theatre Archive University of Bristol

{{DEFAULTSORT:Smith, C. Aubrey 1863 births 1948 deaths Cambridge University cricketers England Test cricketers English male film actors English male silent film actors English male stage actors English expatriate male actors in the United States Actors awarded knighthoods Cricket people awarded knighthoods Cricketers who have taken five wickets on Test debut Knights Bachelor Commanders of the Order of the British Empire England Test cricket captains English cricketers Sussex cricket captains Sussex cricketers People from the City of London Gauteng cricketers Gentlemen cricketers North v South cricketers Legion of Frontiersmen members Deaths from pneumonia in California People educated at Charterhouse School Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge 19th-century English male actors 20th-century English male actors Marylebone Cricket Club cricketers Gentlemen of England cricketers Cricketers who have acted in films Cricketers from Greater London Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer contract players Male actors from London